Little, Brown, & Company

1904

To

Isidore and Elizabeth

Daughters of his friend

Ch. F. Grimmer

INTRODUCTION TO THE ELECTRONIC EDITION

This text is offered as a demonstration of the application of digital text encoding technologies (XML, TEI, XSLT), but also because it is not without interest in itself.

As a demonstration of text encoding, it has several important virtues. First and primarily, it is modern enough to conform in most important respects to contemporary practices in document production and layout. This enables the encoder to set aside many vexing questions of how best to represent material artifacts in electronic media, aiming instead at something like a facsimile. Yet while the text is mostly regular in its organization, it is not entirely so, including several footnotes and a graphic image; despite its regularity it presents several challenges common when translating printed texts into electronic form. Minute though these may be (involving questions such as whether and how to register discriminations between different kinds of titles, cited more or less formally, or how exactly to place page break markers or render them in display), even this serves as a nice demonstration, showing the student of technology how editorial concerns — even in the guise of technical ones — never entirely disappear from what remains essentially an editorial process.

In this near-regularity, the production being emulated here exemplifies a late phase of print technology when, under the pressure of almost fully mechanized composition processes (the original by Little, Brown and Co. was apparently set in hot lead), textual media are becoming increasingly codified and regulated for purposes of automation. (We are mistaken if we identify this trend only with digital technology as such, which reflects and amplifies it.) In this particular case, neither high production values (this is not an art book) nor the more elaborate requirements of a more fully-featured scholarly edition (we have no index, bibliography or apparatus criticus, and even the footnotes are few and rudimentary) obscure the way in which the publishing industry is already, in 1904, promoting clean and simplified forms in design, composition and display, optimized for production processes closer to lights out (the technologist’s slang for an entirely automated system). Thus both continuity and development are discernible between the manuscript written in ink, the codex in the library, and the electronic form this text eventually takes.

If to consider this text is to consider how text itself is evolving, Gustav Fechner's Büchlein vom Leben nach dem Tode interestingly echoes one of its own theses, namely that no understanding of individual human consciousness is possible and meaningful without taking account of consciousness in the large, which itself is undergoing a process of development. Not only is no man an island; no man (or no person, to shift from the male-centric view of both John Donne and Gustav Fechner after him) is a perfectly discrete, separable thing at all. However definite we find it, the fragmentation of consciousness we experience, both between ourselves (to the extent we exercise our capacities for sympathy and understanding) and within each of us (as our awareness, fickle and intemperate, hovers and jumps from thing to thing), is contingent and temporary. This aloneness of which we are so convinced, indeed, is only a necessary step in the realization of the consciousness of the whole, at whatever level the whole is conceived: humankind, the earth, the cosmos.

Anticipating both the spiritualism of the later nineteenth century — Theosophy, New Thought, Anthroposophy — and some aspects of popular New Age philosophies of the present, this doctrine is easy to mistake for woolly-mindedness and wishful thinking. Yet to do so would be to fail to do justice not only to the argument as given, but to ourselves. Much of the interest of Gustav Fechner’s writing here (especially in this sometimes awkward translation) is in how we are challenged to understand its categories of language and thought without the baggage they accrue by later and less careful uses: it relies on metaphor and analogy, requiring interpretation, even as it demands we question what we know. Though William James designates him a philosopher, Fechner is also a scientist even in our sense of that term; and rather than considering him a precursor of the New Age, the reader should perhaps be thinking of General Systems Theory, Cybernetics, and Process Theology — if not of Eastern and Buddhist ideas in which he was also, certainly, unschooled: karma (cause and effect), anātman (self as fiction), dependent origination (pratītyasamutpāda) and awakened mind (bodhicitta). Fechner himself, the reader should not fail to observe, does not hesitate to criticize the contagion of superstition. The root, as he puts it, must be science, founded in skepticism, observation, and critical analysis, of which true faith should be the fruit.

I write at a time when this idea, however unexceptionable it may seem when stated, sounds radical, assuming as we do that science and suppositions regarding life after death or anything like it must have nothing to do with each other. If we think about it at all, we suppose only that science says life after death cannot be — without pausing to wonder what life is, how it gives rise to consciousness (or is it the other way around), or how what we mean by death is implicated in how we define life, thereby turning the very phrase life after death into a logical contradiction in terms. But Fechner takes us back to a moment when Western science was not yet entirely dominated by positivism, materialism or even (what may be more to the point) a supposedly sober impatience with speculation that goes behind or beyond institutionalized methodologies of experiment and discovery. It could be that this impatience, indeed, undermines science and makes it vulnerable (paradoxically) to charges of irrelevance, inasmuch as people continue to insist on their preoccupations with unscientific questions, while on the other hand, imagination and speculation cannot be banished from science without betraying its own foundation in curiosity and wonder. Be that as it may, our culture now takes it for granted that somehow matters of faith should be exempted from the rigors of scientific reasoning, whether faith is expressed in earnest moralizing or in personal suppositions about the greater world beyond the reach of our senses — even while the world beyond our reach continues to retreat as scientific accounts of it become more comprehensive and sophisticated, and technology continues to revolutionize the material conditions of our lives. Thus it is liberating to go along, however tentatively, with a thinker who attempts candidly to be both imaginative and rigorous in speculation, innocent of our own dogmas, discomforts and taboos.

After all, these questions practically beg for a careful and critical questioning of their premises, even while we learn how immeasurably greater is our larger life than the flickering life of any of us in isolation. Let us not fail to notice that these perennial technological revolutions have brought us, at length, to a point where we can consider, as an entirely mundane and practical matter, how to make a text like this one, obscure as it is, available and accessible to anyone in the world in an instant. Ironically, publishing lights out or nearly so means to publish, if not entirely without some modest efforts devoted to abstruse questions of editorial practice and text encoding, yet with the considerable aid of machines, harmonized with our intellects and put to work in a vast collective enterprise in which we are all engaged, every time we glance at one of the luminous screens we have erected in our living rooms or carry in our pockets. These machines would not be working at all were it not for the illumination of such consciousness as we bring to them, whether put to good ends or bad. So Fechner’s Büchlein may be obscure, but the question with which it treats is not; and with its release in this form, its confident yet critical perspective on (what we insist on supposing is) the predicament of our mortality may approach closer to each of us, like the waves of a pebble (as he says) dropped into a pool of water.

INTRODUCTION

I GLADLY accept the translator’s invitation to furnish a few words of introduction to Fechner’s Büchlein vom Leben nach dem Tode, the more so as its somewhat oracularly uttered sentences require, for their proper understanding, a certain acquaintance with their relations to his general system.

Fechner’s name lives in physics as that of one of the earliest and best determiners of electrical constants, also as that of the best systematic defender of the atomic theory. In psychology it is a commonplace to glorify him as the first user of experimental methods, and theviii first aimer at exactitude in facts. In cosmology he is known as the author of a system of evolution which, while taking great account of physical details and mechanical conceptions, makes consciousness correlative to and coeval with the whole physical world. In literature he has made his mark by certain half-humoristic, half-philosophic essays published under the name of Dr. Mises — indeed the present booklet originally appeared under that name. In aesthetics he may lay claim to be the earliest systematically empirical student. In metaphysics he is not only the author of an independently reasoned ethical system, but of a theological theory worked out in great detail. His mind, in short, was one of those multitudinously organizedix crossroads of truth, which are occupied only at rare intervals by children of men, and from which nothing is either too far or too near to be seen in due perspective. Patient observation and daring imagination dwelt hand in hand in Fechner; and perception, reasoning, and feeling all flourished on the largest scale without interfering either with the other’s function.

Fechner was, in fact, a philosopher in the great sense of the term, although he cared so much less than most philosophers do for purely logical abstractions. For him the abstract lived in the concrete; and although he worked as definitely and technically as the narrowest specialist works in each of the many lines of scientific inquiry which he successivelyx followed, he followed each and all of them for the sake of his one overmastering general purpose, the purpose namely of elaborating what he called the daylight view of the world into greater and greater system and completeness.

By the daylight view, as contrasted with the night view, Fechner meant the anti-materialistic view, — the view that the entire material universe, instead of being dead, is inwardly alive and consciously animated. There is hardly a page of his writing that was not probably connected in his mind with this most general of his interests.

Little by little the materialistic generation that called his speculations fantastic has been replaced by one with greater liberty of imagination. Leadersxi of thought, a Paulsen, a Wundt, a Preyer, a Lasswitz, treat Fechner’s pan-psychism as plausible, and write of its author with veneration. Younger men chime in, and Fechner’s philosophy promises to become scientifically fashionable. Imagine a Herbert Spencer who, to the unity of his system and its unceasing touch with facts, should have added a positively religious philosophy instead of Spencer’s dry agnosticism; who should have mingled humor and lightness (even though it were germanic lightness) with his heavier ratiocinations; who should have been no less encyclopedic and far more subtle; who should have shown a personal life as simple and as consecrated to the one pursuit of truth, — imagine this, I say, if you can, and youxii may form some idea of what the name of Fechner is more and more coming to stand for, and of the esteem in which it is more and more held by the studious youth of his native Germany. His belief that the whole material universe is conscious in divers spans and wave lengths, inclusions and envelopments, seems assuredly destined to found a school that will grow more systematic and solidified as time goes on.

The general background of the present dogmatically written little treatise is to be found in the Tagesansicht, in the Zend-Avesta and in various other works of Fechner’s. Once grasp the idealistic notion that inner experience is the reality, and that matter is but a form in which inner experiences mayxiii appear to one another when they affect each other from the outside; and it is easy to believe that consciousness or inner experience never originated, or developed, out of the unconscious, but that it and the physical universe are coeternal aspects of one self-same reality, much as concave and convex are aspects of one curve. Psychophysical movement, as Fechner calls it, is the most pregnant name for all the reality that is. As movement it has a direction; as psychical the direction can be felt as a tendency and as all that lies connected in the way of inner experience with tendencies, — desire, effort, success, for example; while as physical the direction can be defined in spatial terms and formulated mathematically orxiv otherwise in the shape of a descriptive law.

But movements can be superimposed and compounded, the smaller on the greater, as wavelets upon waves. This is as true in the mental as in the physical sphere. Speaking psychologically, we may say that a general wave of consciousness rises out of a subconscious background, and that certain portions of it catch the emphasis, as wavelets catch the light. The whole process is conscious, but the emphatic wave-tips of the consciousness are of such contracted span that they are momentarily insulated from the rest. They realize themselves apart, as a twig might realize itself, and forget the parent tree. Such an insulated bit of experience leaves,xv however, when it passes away, a memory of itself. The residual and subsequent consciousness becomes different for its having occurred. On the physical side we say that the brain-process that corresponded to it altered permanently the future mode of action of the brain.

Now, according to Fechner, our bodies are just wavelets on the surface of the earth. We grow upon the earth as leaves grow upon a tree, and our consciousness arises out of the whole earth- consciousness, — which it forgets to thank, — just as within our consciousness an emphatic experience arises, and makes us forget the whole background of experience without which it could not have come. But as it sinks again into that background it is not forgotten.xvi On the contrary, it is remembered and, as remembered, leads a freer life, for it now combines, itself a conscious idea, with the innumerable, equally conscious ideas of other remembered things. Even so is it, when we die, with the whole system of our outlived experiences. During the life of our body, although they were always elements in the more general enveloping earth-consciousness, yet they themselves were unmindful of the fact. Now, impressed on the whole earth-mind as memories, they lead the life of ideas there, and realize themselves no longer in isolation, but along with all the similar vestiges left by other human lives, entering with these into new combinations, affected anew by experiences of the living, and affecting thexviii living in their turn, enjoying, in short, that third stage of existence with the definition of which the text of the present work begins.

God, for Fechner, is the totalized consciousness of the whole universe, of which the Earth’s consciousness forms an element, just as in turn my human consciousness and yours form elements of the whole earth’s consciousness. As I apprehend Fechner (though I am not sure), the whole Universe — God therefore also — evolves in time: that is, God has a genuine history. Through us as its human organs of experience the earth enriches its inner life, until it also geht zu grunde and becomes immortal in the form of those still wider elements of inner experience which its history is even nowxviii weaving into the total cosmic life of God.

The whole scheme, as the reader sees, is got from the fact that the span of our own inner life alternately contracts and expands. You cannot say where the exact outline of any present state of consciousness lies. It shades into a more general background in which even now other states lie ready to be known. This background is the inner aspect of what physically appear, first, as our residual and only partially excited neural elements, and then more remotely as the whole organism which we call our own.

This indetermination of the partition, this fact of a changing threshold, is the analogy which Fechner generalizes, that is all.

There are many difficulties attaching to his theory. The complexity with which he himself realizes them, and the subtlety with which he meets them are admirable. It is interesting to see how closely his speculations, due to such different motives, and supported by such different arguments, agree with those of some of our own philosophers. Royce’s Gifford lectures, The World and the Individual, Bradley’s Appearance and Reality, and A. E. Taylor’s Elements of Metaphysics, present themselves immediately to one’s mind.

PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION

THE first edition of this little book appeared in the year 1836 under the pen name of Mises and was published by my friend, long since dead, the book dealer and composer, Ch. F. Grimmer. It made its way quietly, like the first edition of its author’s life, of which the little book was a part, while cherishing the expectation of a second. With the years of the one first edition, the copies of the other, without being yet quite exhausted, are diminishing.

While I dedicate this second edition, issued from another friendly publishingxxii house, and under my own name, to the beloved daughters of my departed friend, in whom is continued for us that knew him all that we loved in him, I believe, in the sense of the very view which is set forth in this book, that I am giving it back to my friend in the way he would best like. He has, indeed, a perpetual spiritual claim upon the earlier material; for it originated mainly as the result of talks with him about an idea of our mutual friend Billroth, which, though cursorily expressed and held by the latter, yet took deep root in the heart of the author. It was a little seed, a tree has grown from it; he has helped to loosen the earth for it.

Let me here add a wish: that there might be a revival of my friend’s songs,xxiii so beautiful and so forgotten, as well as of this half-forgotten little book. The creation of both went on so hand in hand during a period of daily companionship, that they seem to echo and re-echo in my memory like intermingled melodies. Simple as their charm is, may they have a duration even beyond that of the music of the future; for sound drowns beauty, yet beauty outlives sound, and what begins loud cannot so end. But if I did not believe that the same is true of truth as of beauty, how should I hope for a future for the opinions of this book?

The reason for exchanging the former pen name now for the author’s own, was personal. The little paper at its first appearance was a divergence from thexxiv chief characteristics of the author’s other works; but it became the firstling of a series of later writings, appearing under his own name, which, in their contents, conform to it more or less, and to which it may therefore be added by the ascription of a common origin. Finally, their grouping results from the consideration that they combine with the work before us to form a connected theory of life which partly supports, partly is supported by the contents of this book. A further carrying out of this view, only briefly developed here, may be found in the third part of the Zend-Avesta.

This edition has only been altered in unimportant respects, extended in several, from the former.

PREFACE TO THE THIRD EDITION

IT is sufficient to remark that, except by the addition of a note upon page 57, and the omission of an easily controverted appendix (on the principle of divine vision) at the close of the last edition, the present one only differs from the former in unimportant changes of a few words.

The fourth edition, the first after the author’s death, is a faithfully rendered reprint of the third, changed only in form.

APPENDIX TO THE FIRST EDITION

THE first suggestion of the idea worked out in this paper, that the spirits of the dead continue to exist in the living as individuals, came to me through a conversation with my friend Professor Billroth, then living in Leipzig, now in Halle. While this idea, in a series of related images, both appealed to me and awakened kindred ones, it took prominent shape, and through a sort of enforced progression extended to the idea of a higher life of spirits in God. Meanwhile the originator, as in the philosophy of religionxxviii in general, so especially in the doctrine of immortality, took a quite different line from this, conforming more directly to the church dogma, which led him away, for the most part, if not wholly, from this fundamental idea, so that, while I had thought it necessary to point to him as its author, I no longer venture to call him its advocate. The views of this philosopher upon the subject in question will be developed in a work by him shortly to appear.

LIFE AFTER DEATH

CHAPTER I

MAN lives upon the earth not once, but three times. His first stage of life is a continuous sleep; the second is an alternation between sleeping and waking; the third is an eternal waking.

In the first stage man lives alone in darkness; in the second he lives with companions, near and among others, but detached and in a light which pictures for him the exterior; in the third his life is merged with that of other souls into the higher life of the Supreme2 Spirit, and he discerns the reality of ultimate things.

In the first stage the body is developed from the germ and evolves its equipment for the second; in the second the spirit unfolds from its seedbud and realizes its powers for the third; in the third is developed the divine spark which lies in every human soul, and which, already here through perception, faith, feeling, the intuition of Genius, demonstrates the world beyond man to the soul in the third stage as clear as day, though to us obscure.

The passing from the first to the second stage is called birth; the transition from the second to the third is called death.

The way upon which we pass from the second to the third stage is not3 darker than that by which we reach the second from the first. The one leads to the outer, the other to the inner aspect of the world.

But as the child in the first stage is still blind and deaf to all the glory and joy of the life of the second, and his birth from the warm body of his mother is hard and painful, with a moment when the dissolution of his earlier existence feels like death, before the awakening to the new environment without has occurred, — so we in our present existence, in which our whole consciousness lies bound in our contracted body, as yet know nothing of the splendor and harmony, the radiance and freedom of the third stage, and easily hold the dark and narrow way which leads us into it as a blind pitfall which has no4 outlet. But death is only a second birth into a freer existence, in which the spirit breaks through its slender covering and abandons inaction and sloth, as the child does in its first birth.

Then all, which with our present senses only reaches us as exterior and, as it were, from afar, we become penetrated with and possessed of in all its depth of reality. The spirit will no longer wander over mountain and field, or be surrounded by the delights of spring, only to mourn that it all seems exterior to him; but, transcending earthly limitations, he will feel new strength and joy in growing. He will no longer struggle by persuasive words to produce a thought in others, but in the immediate influence of souls upon5 each other, no longer separated by the body, but united spiritually, he will experience the joy of creative thought; he will not outwardly appear to the loved ones left behind, but will dwell in their inmost souls, and think and act in and through them.

CHAPTER II

THE unborn child has merely a corporeal frame, a forming principle. The creation and development of its limbs by which it reaches full growth are its own acts. It has not yet the feeling that these parts are its possession, for it needs them not and cannot use them. A fine eye, a beautiful mouth, are to him only objects to be secured unconsciously, so that they may sometime become serviceable parts of himself. They are made for a subsequent world of which the child as yet knows nothing: it fashions them by virtue of an impulse, blind to him, which is clearly7 established alone in the organization of the mother.1 But when the child, ripe for the second stage of life, slips away from the organ representing the provision8 for his former needs, it leaves it behind, and suddenly sees itself an independent union of all its created parts. This eye, ear, and mouth now belong to him; and even if acquired only through an obscure inborn sense, he is learning to know their precious uses. The world of light, color, tone, perfume, taste, and feeling is only now revealed as the arena in which the functions acquired to that end are to operate for him, if he makes them serviceable and strong.

1. It may thus be more clearly stated to the physiologist: The creative principle of the child lies, before birth, not in that which after birth will continue to live on with him, which indeed now is only dependence, the product, but in that which at birth will remain behind and be cast off, like the body of man in death (placenta cum puniculo umbilicali, velamentis ovi eorumque liquoribus): out of its activity emerges, as its continuation, the young human being.

[In the embryonic period it seemed to the child that the placenta was its body, and it was actually its special embryonic body, useless in another stage, and rejected as refuse at the moment of birth. Our body in human life is like a second envelope which is useless to the third life, and for this reason we reject it at the moment of our second birth. Human life as compared with the celestial is truly embryonic. ELIPHAS LEVI.]

The translator.

The relation of the first stage to the second recurs in a higher degree in the relations of the second to the third. Our whole action and will in this world is exactly calculated to procure for us an organism, which, in the next world, we shall perceive and use as our Self. All spiritual influences, all results of9 the manifestations which in the lifetime of a man go forth from him, to be interwoven with humanity and nature, are already united by a secret and invisible bond; they are the spiritual limbs of the man, which he exercises during life while still bound to a spiritual body, to an organism full of unsatisfied, up-reaching powers and activities, the consciousness of which still lies outside him, though inseparably interwoven with his present existence, yet, only in abandoning this, can he recognize it as his own.

But in the moment of death, when the man is separated from the organ upon which his acquisitive efforts were bent here, he suddenly receives the consciousness of all, which as a result of his earlier exterior life in the world10 of ideas, powers, and activities, still survives, prevails, flowing out as from a wellspring, while still bearing also within himself his organic unity.

This, however, now becomes living, conscious, independent, and, according to his destiny, controls mankind and nature with his own completed individual power.

Whatever anyone has contributed during his life, of creation, formation, or preservation, to the sum of human idealism, is his immortal part, which, in the third stage, will continue to operate even if the body, to which, in the second, this working power was bound, were long since destroyed. What millions who have died have acquired, performed, and thought, has not died with them — nor will it be undone by11 what the next millions shall have acquired, performed, and thought, but continues its power, unfolds itself in them spontaneously, impels them towards a great goal which they do not themselves perceive.

This ideal survival seems indeed to us only an abstraction, and the continued influence of the soul of the dead in the living but an empty fancy.

But it only appears so to us because we have no power to perceive in them spirits in the third stage, to comprehend a predestined and permanent existence; we can only recognize the connecting link of their existence with ours, the portion of increase within us, appearing under the form of those ideas which have been transmitted from them to us. Although the undulating circle12 which a sinking stone leaves behind it in the water creates, by its contact, a new circle around every rock which still projects above the surface, it still retains in itself a connected circumference which stirs and carries all within its reach; but the rocks are only aware of the breaking of the perfect line. We are just such ignorant objects, only that we, unlike fixed rocks, while even still in life, shed about us a continuous flow of influence which extends itself not only around others but within them.

Already, in fact, during his lifetime, every man with his influence grows into others through word, example, writing, and deed. While Goethe lived, contemporary millions bore within them sparks from his soul, and were thereby newly kindled. In Napoleon’s life nearly 13 the whole period was penetrated by the force of his spirit. With their death these tributary sources of life did not also die; only the motive power of a new earth-born channel expired, and the growth and manifestation of this, emanating from an individual, and in their totality again forming an individual, production now takes place with a similar indwelling consciousness, incomprehensible indeed to us, as was its first inception. A Goethe, a Schiller, a Napoleon, a Luther, still live among us, thinking and acting in us, as awakened creative individuals, more highly developed than at their death — each no longer restrained by the limitations of the body, but poured forth upon the world which in their lifetime they molded, gladdened, swayed, and in their personality14 far surpassing the influences which we still discern as coming from them.

The greatest example of a mighty soul which still lives on actively in after ages is Christ. It is not an empty saying that Christ lives on in his followers; every true Christian holds him not only relatively but absolutely within his heart. Every one is a partaker in him who acts and thinks in obedience to his law, for it is the Christ that prompts this thinking and acting in each. He has extended his influence through all the members of his Church and all cling together through his Spirit, like the apple to its stem, the branches to the vine. For as the body is one, and hath many members, and all the members of that one body, being15 many, are one body: so also is Christ. (1 Cor. xii. 12.2) Yet not only the greatest souls, but every strong man awakes in the next world in conscious though incomplete possession of an organism which is a union of eternal spiritual acquirements and influences, with a greater or smaller extent of realization, and more or less power to unfold further, according as the soul of the man himself in his lifetime has advanced and gained ground. But he who has clung to the earth, and has only used his powers in pursuit of the material life, the pleasures and needs of the body, will find but an insignificant16 remnant of life surviving. And so the richest will become the poorest if he has only his gold to lean upon, and the poorest the richest if he uses his strength to win his life honestly. For what each does here he will have there, and money there will only count for what it brought the consumer here.

2. Many biblical parallels similar to this are placed together in Zend-Avesta III. p. 363, and drei Motiven und Grunden des Glaubens, p. 178.

The problems of our present spiritual life, the thirst for the discovery of truth, which here seems to profit us but little, the striving of every genuine soul to accomplish things which are merely for the good of posterity, conscience, and the repentance that arouses in us an unfathomable distress for bad actions, even though they bring us no disadvantage here, rise from haunting presentiments of what all this will bring to us in that world in which the fruit17 of our slightest and most hidden activity becomes a part of our true self.

This is the great justice of creation, that every one makes for himself the conditions of his future life. Deeds will not be requited to the man through exterior rewards or punishments; there is no heaven and no hell in the usual sense of the Christian, the Jew, the heathen, into which the soul may enter after death. It makes neither a spring upward nor a fall downward, nor comes to a standstill; it does not break asunder, nor dissolve into the universal; but, after it has passed through the great transition, death, it unfolds itself according to the unalterable law of nature upon earth; steadily advancing step by step, and quietly approaching and entering into a higher18 existence. And, according as the man has been good or bad, has behaved nobly or basely, was industrious or idle, will he find himself possessed of an organism, healthy or sick, beautiful or hateful, strong or weak, in the world to come, and his free activity in this world will determine his relation to other souls, his destiny, his capacity and talents for further progress in that world.

Therefore be active and brave. For the idler here will halt there, the earthbound will be of a dull and weak countenance, and the false and wicked will feel the discord which his presence makes in the company of true and pure spirits as a pain, which, even in that world, will still impel him to amend and cure the evil which he has committed in this, and will allow him no peace nor19 rest until he has wiped out and atoned for his smallest and latest evil deed.

And if his companion spirits have for long rested in God, or rather lived as partakers in His thoughts, he will still be pursued by the tribulation and restlessness of the earthly life, and his spiritual disorder will torment men with ideas of error and superstition, lead them into vice and folly, and while he himself is retarded on his way to achievement in the third stage, he also will hold back those in whom he survives, upon their path from the second to the third.

But however long the false, the evil, and the base may still prevail and struggle for its life with the true, the beautiful, and the good, — yet through the ever-increasing power of truth, and20 the growing force of evil’s own self-destructive results, it will at last be conquered and abolished; and so of all falsehood, all evil, all impurity in the soul of man, there will at last be nothing left. That alone is the eternal, imperishable part of a man that is to him true, beautiful, and good. And if only a grain of mustard seed of it is in him — there could be no one without it — so, purged of chaff and dross through the purgatory of life, afflicting only the imperfect, it will survive in the third stage, and, even if late, be able to grow into a noble tree.

Rejoice then, even you whose soul is here tried by tribulation and sorrow; the discipline will avail much, which in the brave struggle with obstacles in the21 path of progress you have experienced in this life, and, born into the new life with more strength, you will more quickly and joyfully recover what fate has denied you here.

CHAPTER III

MAN uses many means to one end; God one means to many ends.

The plant thinks it is in its place for its own purpose, to grow, to toss in the wind, to drink in light and air, to prepare fragance and color for its own adornment, to play with beetles and bees. It is indeed there for itself, but at the same time it is only one pore of the earth, in which light, air, and water meet and mingle in processes important to the whole earthly life; it is there in order that the earth may exhale, breathe, weave for itself a green garment and provide nourishment, raiment23 and warmth for men and animals. Man thinks that he is in his place for himself alone, for amusement, for work, and getting his bodily and mental growth; he, too, is indeed there for himself; but his body and mind are also but a dwelling place into which new and higher impulses enter, mingle, and develop, and engage in all sorts of processes together, which both constitute the feeling and thinking of the man, and have their higher meaning for the third stage of life.

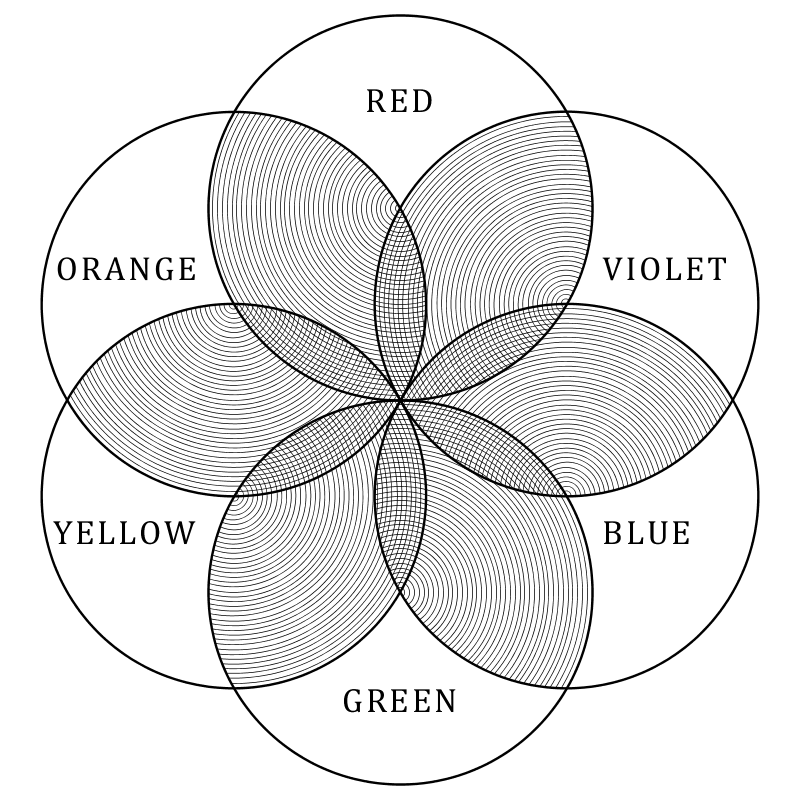

The mind of man is alike indistinguishably his own possession and that of the higher intelligences, and what proceeds from it belongs equally to both always, but in different ways. Just as in this figure, which is intended not for a representation but only a24 symbol, the central, colored, six-rayed star (looking black here) can be considered as independent and having unity in itself; its rays proceeding from the middle point are all thereby dependently and harmoniously bound together; on the other hand, it appears again mingled together from the concatenation of the six single colored circles, each one25 of which has its own individuality. And as each of its rays belongs as well to it as to the circles, through the overlapping of which it is formed, so is it with the human soul.

Man does not often know from whence his thoughts come to him: he is seized with a longing, a foreboding, or a joy, which he is quite unable to account for; he is urged to a force of activity, or a voice warns him away from it, without his being conscious of any special cause. These are the visitations of spirits, which think and act in him from another center than his own. Their influence is even more manifest in us, when, in abnormal conditions (clairvoyance or mental disorder) the really mutual relation of dependence between them and us is determined in their favor, so that we26 only passively receive what flows into us from them, without return on our part.

But so long as the human soul is awake and healthy, it is not the weak plaything or product of the spirits which grow into it or of which it appears to be made up, but precisely that which unites these spirits, the invisible center, possessing primitive living energy, full of spiritual power of attraction, in which all unite, intersect, and through mutual communication engender thoughts in each other, this is not brought into being by the mingling of the spirits, but is inborn in man at his birth; and free will, self-determination, consciousness, reason, and the foundation of all spiritual power are contained herein. But at birth all this lies still latent within, like an unopened seed, awaiting27 development into an organism full of vital individual activity.

So when man has entered into life other spirits perceive it and press forward from all sides and seek to add his strength to theirs in order to reinforce their own power, but while this is successful, their power becomes at the same time the possession of the human soul itself, is incorporated with it and assists its development.

The outside spirits established within a man are quite as much subjected to the influence of the human will, though in a different way, as man is dependent upon them; he can, from the center of his spiritual being, equally well produce new growth in the spirits united to him within, as these can definitely influence his deepest life; but in harmoniously28 developed spiritual life no one will has the mastery over another. As every outside spirit has only a part of itself in common with a single human being, so can the will of the single man have a suggestive influence alone upon a spirit which with its whole remaining part lies outside the man; and since every human mind contains within itself something in common with widely differing outside spirits, so too can the will of a single one among them have only a quickening influence upon the whole man, and only when he, with free choice, wholly denies himself to single spirits is he deprived of the capacity to master them.

All spirits cannot be united indiscriminately in the same soul; therefore the good and bad, the true and false29 spirits contend together for possession of it, and the one who conquers in the struggle holds the ground.

The interior discord which so often finds place in men is nothing but this conflict of outside spirits who wish to get possession of his will, his reason, in short, his whole innermost being. As the man feels the agreement of spirits within him as rest, clearness, harmony, and safety, he is also conscious of their discord as unrest, doubt, vacillation, confusion, enmity, in his heart. But not as a prize won without effort, or as a willing victim, does he fall to the stronger spirits in this contest, but, with a source of self-active strength in the center of his being, he stands between the contending forces within which wish to draw him to themselves,30 and fights on whichever side he chooses; and so he can carry the day even for the weaker impulses, when he joins his strength to theirs against the stronger. The Self of the man remains unendangered so long as he preserves the inborn freedom of his power and does not become tired of using it. As often, however, as he becomes subject to evil spirits, is it because the development of his interior strength is hindered by discouragement, and so, to become bad, it is often only necessary to be careless and lazy.

The better the man already is, the easier it is for him to become still better; and the worse he is, so much the more easily is he quite ruined. For the good man has already harbored many good spirits, which are now associated with31 him against the evil ones remaining and those freshly pressing for entrance, and are saving for him his interior strength. The good man does good without weariness, his spirits do it for him; but the bad man must first overcome and subdue by his own will all the evil spirits which have striven against him. Moreover, kin seeks and unites itself to kin, and flees from its opposite when not forced. Good spirits in us attract good spirits outside us, and the evil spirits in us the evil outside. Pure spirits turn gladly to enter a pure soul, and evil without fastens upon the evil within. If only the good spirits in our souls have gained the upper hand, so of itself the last devil still remaining behind in us flees away, he is not secure in good society; and so the soul32 of a good man becomes a pure and heavenly abiding place for happy in-dwelling spirits. But even good spirits, if they despair of winning a soul from the final mastery of evil, desert it, and so it becomes at last a hell, a place fit only for the torments of the damned. For the agony of conscience and the inner desolation and unrest in the soul of the wicked are sorrows which, not they alone, but the condemned spirits within them also, feel in still deeper woe.

CHAPTER IV

WHILE the higher spirits not only dwell in individual men, but each extends itself into many, it is they who unite these men spiritually, whether of one form of faith or truth, of one moral or political leaning. All men who have any spiritual fellowship with each other belong to the body of one and the same spirit together, and follow the ideal which has thereby been born within them, as members one of another. Often an idea lives at one time in a whole nation, often is a mass of men moved to one and the same action; that is a mighty spirit which seizes them all in one contagious34 influence. Not alone, indeed, through the spirits of the dead do these alliances occur, but countless newborn ideas flow from the living to the living; all these ideas, however, which go forth from the living into the world are already parts of its future spiritual organism.

Now when two kindred spirits meet in human life and are merged together through their common sentiments, while simultaneously, through their differing traits, they mutually influence and enrich each other, at the same time the associations, races, nations, to which each first belonged, enter into spiritual association and enrich each other through their spiritual possessions. So the development of the third stage of life in mankind goes on hand in hand35 inseparably with that of the progress of humanity. The gradual formation of the state, of sciences, of the arts, of human intercourse, the growth of this sphere of life to an ever-increasing harmoniously constructed whole, is the result of this union of innumerable spiritual individualities which live in humanity and fashion it into great spiritual organisms.

How otherwise could these glorious realms, based upon such unalterable principles, be formed out of the tangled egotism of individuals, who, with their shortsighted eyes, from the center could see no circumference, and at the circumference could discern no center, if the higher spirits, seeing clearly through the whole, did not control the machinery, and, while they all press around the36 common divine center, and so in their godlike part meet together, also lead the men whom they influenced, united on to higher goals.

But beside the harmony of spirits which meet and fraternize amicably, there is also a conflict of those whose existence is in disagreement, a struggle which will at last wear itself out, so that the eternal in its purity shall alone survive. Traces of this warring of forces are manifested by mankind in the rivalry of systems, in sectarian hatred, in wars and revolutions between princes and people, and the nations among each other.

The mass of men enter into all these great spiritual movements with blind faith, blind obedience, blind hatred and rage; they hear and see nothing with37 their own spiritual ears and eyes; they are driven by alien spirits toward objects and goals of which they themselves know nothing; they allow themselves to be led through slavery, death, and terrible affliction, like a flock following the call of the higher leadership.

There are, indeed, men who engage in this great agitation, acting and leading with clear consciousness and deep purpose. But they are only voluntary means to great predestined ends; being able, indeed, through their free action to determine the quality and rapidity, but not the goal of progress. Those only have had great influence in the world who have recognized the spiritual tendency of the time in which they lived and have directed their free action and thought into that tendency: equally38 strong men who have resisted it have been overthrown. Every one who has set before him higher aims, and knows better ways thither, has chosen a new central point for his motive power; not as a blind tool, but as one who from his own impulse and understanding serves righteousness and wisdom. The browbeaten slave does not render the best service. But in whatever way men begin to serve God here they will carry further there, as partakers of His divine glory.

CHAPTER V

IT is, indeed, possible for the spirits of the living and the dead to meet unconsciously in many ways, and also consciously only on one side. Who can pursue and trace out this whole line of communication? Let us say briefly: they meet together when in mutual consciousness, and the dead are present wherever they are so consciously.

One means there is of attaining the highest conscious meeting between the living and the dead; it is the memory of the living for the dead. To direct our attention to the dead is to awaken theirs to us, just as a charm which40 is found in a living person encourages a corresponding attraction toward the one perceiving it.

Although our memory of the dead is but a new consciousness, in retrospect, of the results of their known life here, yet the life on the other side will be led conformably to that in this world.

Even when one living person thinks of another, a conscious mutual impulse may be aroused: but it is inoperative because of the still present confines of the body. Once released, however, by death, that consciousness seeks its own realm and is then borne upon a current the more swift and strong, as it has previously been exerted and manifested with frequency and power.

Now just as one and the same physical blow is felt at the same time by41 the giver and the receiver, so is it but a single shock of consciousness that is experienced on both sides when one recalls the dead to memory. Realizing alone this earthly side of consciousness, we err because we fail to discern the other: and this failure brings results of error and loss.

One beloved person is parted from another, a wife from a husband, a mother from a child. In vain do they search in a distant heaven the part of their lives that has been torn from them; in vain they reach out into the void with eye and hand after that which in reality has never been taken away from them; because out of the exterior relations of mutual adjustment and understanding, the threads of which are now broken, has sprung out of the42 depths of interior consciousness a deep and unobstructed union, as yet unfamiliar and unrecognized.

I saw once a mother anxiously seeking through garden and house for her living child which she was carrying in her arms. Still more mistaken is he who seeks for his dead in a remote and deserted place, when he had but to look within to find him still present. And if she does not find him wholly there, did the mother then completely possess her child even while she was carrying him in her arms? The satisfactions of the outward relations, the spoken word, the glance of the eye, the personal care, she can no more have or give; now for the first time she has those of the inner life; she must simply recognize that there is such an interior43 relation with its advantages. No word is spoken, no hand extended to the one who we think is not present. But if we knew all, a new life is to begin for the living and the dead, and the dead gain thereby as well as the living.

If we think of the dead rightly, not merely holding him in mind, he is at that moment present. If you can deeply summon him, he must come, if you hold him fast, he must remain, if sense and thought are strong enough to bind and retain him. And he will perceive whether we think of him with love or with hatred; and the stronger the love or the stronger the hatred, the more clearly he will discern it. Once, indeed, you had a remembrance of the dead — now you are able to use that remembrance; you can still knowingly44 bless or torment the dead with your memories, be reconciled to them or remain in a state of conflict — not alone consciously to you but also to them. Have the best constantly in mind, and be careful only that the memory that you yourself are to leave behind shall be a blessing to you in the future. Well for him who leaves behind him a treasure of love, esteem, honor, and admiration in the memory of men. Such enrichment is his gain in death, since he acquires the condensed consciousness of the whole earthly estimate concerning him; he grasps in full measure the bushel, of which in life he could count but a few kernels. This belongs to the treasure which we are to lay up in heaven.

Woe to him who is followed by execration,45 cursing, and a memory full of dread. Those whom he influenced in this life will not release him in death; this belongs to the hell which is awaiting him. Every reproach that pursues him is like an arrow which, with sure aim, enters into his inmost soul.

But only in the totality of results which evolves itself from good and evil alike is justice fulfilled. The righteous who were here misunderstood must inevitably suffer from it there as from a misfortune; and to the unrighteous an unjust reputation will serve as an outward advantage; therefore, keep your good name as pure as possible here below and hide not thy light under a bushel. But among the spirits in that other sphere even misunderstanding shall cease; what was here held as false46 shall there be found true and by increase be given additional weight. Divine justice overcomes at last all human injustice.

Whatever awakens the memory of the dead is a means of calling them to us.

At every festival which we devote to them they rise up; they float about every monument which we raise to them; they listen to every song with which we praise their deeds. A life germ for a new art! How antiquated had these old dramas become, produced over and over again to the weary spectators. Now all at once, above the ground floor with its expanse of old onlookers, there is revealed, as it were, an encircling realm from which a higher company is seen to be looking down,47 and straightway it becomes the highest aim of men to grow into the likeness of those above rather than those below, to realize, not the desires of those below, but of those above.

The scoffers scoff and the churches contend. It is a question of a secret, irrational to some, rational to others, both because to one and the other a greater mystery remains unrevealed, from the disclosure of which comes quite clearly and obviously the rock upon which the mind of the scoffer and the unity of the church have been wrecked. For it is only a supreme example of a universal law in which they discern an exception to and above all laws.

Not alone through the consecrated bread and wine does Christ reach His48 followers at the Holy Supper; partake of it in pure remembrance of Him, and He, with His thought, will be not only with you, but in you; the more deeply, as you hold Him more closely in your heart; the more vitally, with so much the more strength will He fortify you; yet, without communion with Him, the sacrament remains but meal and water and common wine.

CHAPTER VI

THE longing in every man to meet again after death those who were most dear to him here, to have communication with them, renewing the old relations, will be satisfied in a more perfect degree than was ever anticipated or hoped for.

For in that life those who were united here by a common spiritual bond will not only meet but will have become one through this bond; there will be for them a unified soul belonging with a common consciousness to both. For already, indeed, are the dead with the living, as are the living themselves, bound together by countless such common 50 ties; but only when death loosens the knot and removes the body which envelops every living soul, will there be added to the union of consciousness the consciousness of union.

Everyone in the moment of death will perceive that he still has a place and belongs in the company with those gone before, from whom through common interests he has received help, and so will not enter into the third world as a strange guest, but like one long expected, to whom all with whom he was here united through a common faith, knowledge, and love, will stretch out their hands to draw him to themselves as a partaker of their existence.

Into similar deep fellowship shall we also enter with those great dead who long before our time wandered through51 the second stage of life, and upon whose example and teaching our own spirit was moulded. So, whoever here lived wholly in Christ will there be also wholly in Him. Yet his individuality will not be extinguished in the higher one, but only gain in power from it, and at the same time reinforce the strength of the higher. For those souls which have grown together as one through their moments of sympathy, gain force each from the other for itself, and at the same time confirmation as individuals through the union of their diversities.

So, many souls will mutually strengthen each other in the greater part of their nature; others are connected only by a few corresponding qualities.

Not all these ties based upon certain52 spiritual experiences in common will be permanent, but they will be so when they are within the realm of truth, beauty, and virtue.

All that does not bear within itself eternal harmony, even if it survives this life, will yet at last come to naught and will cause a separation of those souls which for a time had been united in an unworthy alliance.

Most spiritual perceptions which are developed in the present life, and which we take over into the next, bear, it is true, a germ of truth, goodness, and virtue within themselves, but enveloped in a large addition of unessential falseness, error, and corruption. Those spirits which remain united through such impulses may so continue or they may separate, according as they both agree53 to hold fast to the good and the best, and to abandon the evil by their separation from evil spirits, or according as one seizes on the good and the other on the evil.

Those souls, however, which have seized together upon a form or an idea of truth, beauty, or goodness in their eternal purity, remain thereby united to all eternity and in like manner possess these ideals as a part of themselves in everlasting unity.

The comprehension of the higher thought by advanced souls means therefore their growth through this thought into greater spiritual organisms, and as all individual ideas have their root in the universal, so at last will all souls, in fellowship with the highest, be absorbed into the divine.

The spiritual world in its consummation will therefore be, not an assembly, but a tree of souls, the root of which is planted on earth and whose summit reaches to the heavens.

Only the highest and noblest spirits, Christ, the geniuses, the saints, are able to reach, out of their full knowledge, the center of divinity face to face; the smaller and lesser ones have their roots in these, as boughs in branches and twigs in boughs, and are thus connected midway indirectly through them with the highest of the high.

And so dead geniuses and saints are the true mediators between God and man; partaking of the thought of God they are able to convey it to man, and at the same time feeling and understanding human sorrows, joys, and55 desires, they are able to lead him to God.

Yet the worship of the dead stands in relation to the deified worship of nature, at the very beginning of religion, half related and half separated; the most savage nations have retained it in its cruder, the most civilized in its higher form. And where today is there one which does not preserve a large fragment of it as its cornerstone?

And so there should be in every town a shrine for its greatest dead, built near or in the temple of God, and let Christ as heretofore dwell in the same temple as God himself.

CHAPTER VII

MAN lives here at once an outer and an inner life, the first all visible and audible in look, word, writing, in outward affairs and works, the last perceptible to himself only through interior thoughts and feelings. The continuation of the visible into the exterior is easily followed; the development of the unseen remains itself invisible, but yet goes on. Rather the inner life of man progresses, with his outer life, as57 its nucleus, to form the nucleus of the future life.

In fact, that which goes out visibly and perceptibly from man during his lifetime is not the only thing that emanates from him. However small and fine the vibration or impulse may be by which a conscious emotion is carried to our minds, yet the whole play of conscious emotions is borne by an inward mental action, it cannot die out without producing effects of its kind in us and at last beyond us; only we cannot follow them into life outside. As little as can the lute keep its playing to itself, it is borne out beyond it, so little can our minds; to the lute or the mind belongs only that which is closest to it. What an infinitely complex play of subtle waves having their origin in our58 minds may spread itself over the gross lower realm of action, perceptible to the outward eye and ear, like the fine ripples on the large waves of a pond, or the flat designs on the surface of a closely woven carpet, which takes from them its whole beauty and higher meaning. The physicist, however, recognizes and follows only the action of the lower exterior order, and does not concern himself with the finer, which he does not perceive. But even if he does not perceive it, yet knowing the principle, does he dare deny the result?3

3. Whether one attributes nervous energy to a chemical or an electrical process, one must still regard it, if not simply as the play of the vibration of minutest atoms, yet as in the main excited or accompanied by this, whereby the imponderable has a larger part than the ponderable. Vibrations, however, can only apparently expire by extending themselves into their environment, or if indeed they disappear for a time through translation of their living strength into so-called elasticity, yet, according to the law of the conservation of energy, they await a revival in some other form.

Therefore, what we have absorbed from souls through the influences of their outward perceptible life in this world does not yet comprise their whole being; but, in a way incomprehensible to us, there still remains in their nature, besides that outward part, a deeper, indeed the chief part of their existence. And if a man had spent and ended his life on a desert island without ever having come in contact with another human life, he would have firmly retained his inner existence, awaiting a future development, which in this world he60 could not find through intercourse with others. If on the other hand a child had lived but a moment, it could not die again in eternity. The least impulse of conscious life surrounds itself with a circle of influences, just as the briefest tone, which in a moment seems to die, throws out vibrations which reach out into infinity, beyond those standing near by and listening; for no influence expires in itself, and each produces others of its kind into eternity. And so will the soul of the child go on developing from this conscious beginning like that of the man left in isolation, only otherwise than as if beginning from an already advanced development.

Now, just as man in death first receives the full consciousness of what he has produced spiritually in others, so also61 in death will he acquire for the first time complete knowledge and use of what he has cultivated in himself. Whatever he has gathered during life of spiritual treasure, what fills his memory or penetrates his feeling, what his intelligence and imagination have created, remain forever his! Yet its whole connection remains dark in this life; thought merely passes through with a light-giving ray and illuminates what lies on the narrow line of his life, the rest remaining in obscurity. The soul here below never realizes all at once the entire depth of its fullness; only when one of its impulses draws another into union with itself does it emerge for an instant from the darkness, only to sink back again in the next. So man is a stranger to his own soul and wanders62 about within it as he may, or wearily seeking the way to his life’s end, and often forgets his best treasures, which, aside from the glowing path of thought, lie sunken in the darkness which covers the wide region of his soul. But in the moment of death, in which an eternal night darkens the eye of his body, light will begin to dawn in his soul. Then will the center of the inner man kindle into a sun which illuminates his whole spiritual nature, and at the same time penetrates it as with an inner eye, with divine clearness. All which was here forgotten will he recover there, indeed he only forgot it here because it went before him into the other world; now he finds it again collected. In that new universal luminousness he will no longer be obliged to seek out wearily63 what he would fain appropriate, separating his own from what he must reject, but at a glance he is able to understand himself wholly, and at the same time to perceive the true relations between unity and diversity, connection and separation, harmony and discord, not only according to one line of thought but equally according to all.4 As far as are the flight and vision of the bird above the slow crawling of the blind worm which perceives nothing beyond what its sluggish body touches, so greatly64 will the higher knowledge transcend that of the present. And so in death, with the body of man will also pass away his mind, his understanding, indeed the whole finite dwelling place of his soul, as forms become too narrow for its existence, as parts which are of no further use in an order of things in which all knowledge which they had to seek and discover gradually, laboriously, and imperfectly, he now has openly revealed, possessed, and enjoyed. The self of man, however, will subsist unimpaired in its full extent and development through the destruction of its transitory forms, and, in the place of that extinct lower sphere of activity, will enter into a higher life. Stilled is all restlessness of thought, which no longer needs to seek in order to find65 itself, or to approach another to come into conscious mutual relations. Rather begins now a higher interchange of spiritual life; as in our own minds thoughts interchange together, so between advanced souls there is a fellowship, the all-embracing center of which we call God, and the play of our thoughts is but tributary to this high communion. Speech will no longer be needed there for mutual understanding, and no eye for recognition of others, but as thought in us comprehends and relates itself to thought, without the medium of ear, mouth, or hand, unites or separates without exterior restraint or prohibition, so comforting, intimate, and untrammelled will mutual spiritual communication be, and nothing will remain hidden in one from the other. All66 sinful thoughts which here slink away into the dark places of the mind, and all which man would be glad to cover up from his kind with a thousand hands, become known to all. And only the soul which has been quite pure and true here can without shame come into the presence of others in that world; and he who has been misunderstood here on earth will there find recognition.

4. Even in this world, at the approach of death (by narcotics, in imminent drowning, or in exaltation) there occur flashes of recognition of the spiritual meaning of things, examples of which are recorded in Zend-Avesta III. s. 27, and (cases of threatened drowning) in Fechner’s Centralblatt für Naturwiss. und Anthropologie, 1853, s. 43 u. 623.

And even in its individual life will the soul through self-inspection become aware of every deficiency and every remnant, left behind from this life, of imperfection, disturbance, and discord, and not only will it recognize these defects, but feel them, all in common, with the same force as we our bodily infirmities. But as thoughts can be cleansed from all that is unworthy, and67 in moments of insight be united to still higher thoughts, each becoming thereby perfected in that which was lacking, even so will souls in their mutual intercourse find the path of progress to wards perfection.

CHAPTER VIII

DURING his lifetime man has not only spiritual but also material relations with nature. Heat, air, water, and earth press upon him from all sides, and go out from him back again, creating and transforming his body; but as these elements, which outside of man only operate side by side, meet and mingle in him, they form a combination, that of man’s bodily sensation, and at once this bodily sensation cuts off man’s inner being from the sensations of the outer world. Only through the windows of the senses is man able to look out from his bodily frame and realize the outer world and, as it were, in69 small handfuls to draw something from it.

But when man dies, with the destruction of his body that combination is loosened, and, released from its bondage to it, the soul will now return to nature with full freedom. He will no longer be conscious of the waves of light and sound only as they strike eye and ear, but, as the waves roll forth into the sea of ether and the sea of air, he will not merely feel the blowing of the wind and the wash of the waves against his body, but will himself murmur in the air and sea; no more wander outwardly through verdant woods and meadows, but himself consciously pervade both wood and meadow and those wandering there.

Therefore nothing is lost to him in the transition to the higher stage, except70 implements, the limited use of which he can dispense with in an existence in which he will carry and perceive within himself fully and directly all which in the lower stage came to him only fitfully and superficially through their dull mediation. Why should we take over into the life to come eye or ear to obtain light and sound from the spring of living nature, when the current of our future life will merge as one with the waves of light and sound. Even more!

The human eye is only a little radiant spot upon the earth, and only gets the impression in the firmament of points of light. Man’s longing to know more of the universe is not here gratified.

He discovers the telescope and magnifies with it the surface, and so the71 capacity of his eye; in vain, the stars still remain little points.

Now he believes that he will attain in the next world what this life cannot grant, the final satisfaction of his curiosity; that once in heaven he will immediately perceive all that has been hidden from his earthly eyes.

He is right; but he does not reach a heaven because he receives wings to fly from one planet to another or even into an unseen heaven over the visible one; where in the nature of things could wings exist to that end? He does not learn to know the whole universe, by being slowly borne from one planet to another in ever-repeated birth; no stork is there to carry children from one star to another; his eye does not gain the capacity for72 the infinite ethereal depths by being made into a great telescope; the principle of earthly sight will no longer suffice; — yet he will attain to all, in that, as a conscious part of the other life in the great heavenly existence that holds him, he wins a place in its high fellowship with other divinely illuminated beings. A new vision! Not for us here below, because no one of us has reached that plane. In the firmament the earth itself swims like a great eye wholly immersed in the vast star spaces, and swinging around therein, to receive from all sides the impact of waves which cross each other millions and millions of times and yet cause no disturbance. With this eye will man some time learn to discern the heavens, while the forward surging of his future life, with73 which he pierces it, meets and presses against the wave of the surrounding ether, and with finest pulsations penetrates the universe. Learn to see! And how much will man have to learn after death! For he must not think that, at the first entrance, he will possess the whole divine perception for which the future life will offer him the means. Even here the child first learns to see and hear; for what he sees and hears in the beginning is uncomprehended appearance, is mere sound without meaning — at first indeed only bewilderment, astonishment, and confusion; and nothing different does the new life offer to the new child at first. Only what man brings with him from this life, the composite echo of memories of all he has done and thought and been here,74 does he see, in the transition, all at once clearly lighted up within itself, yet still he remains primarily only what he was. Neither does anyone think that the glory of the other world shall result otherwise to the foolish, the idle, and the bad, than to make them feel the discord of their lives, and to emphasize the necessity for reform. Already in the present life man brings with him an eye to behold the whole glory of heaven and earth, an ear to hear music and the speech of man, an understanding to grasp the meaning of all this; what does it avail to the foolish, the indolent, and the bad?

As the best and the highest in this life so is also the best and the highest in the other only there for the best and the highest, because alone by such75 understood, wished for, and acquired. Therefore, the higher man of the next world alone can gain a comprehension of the conscious intercourse in the existence into which he has passed with other divine beings, entering with them himself into this fellowship.

Who knows whether the whole earth, revolving in an ever slowly narrowing orbit, will not return to the heart of the sun from which it came, after eons of years, and then a sun life of all earthly creatures will begin; and where is the need of our knowing this now?

CHAPTER IX

SPIRITS of the third stage will dwell, as in a common body, in the earthly nature, of which mankind itself is a part, and all natural processes will be the same to them as they are to us in our bodies. Their substance will encompass the forms of the second stage as a common mother, just as those of the second stage surrounded those of the first.

Every soul of the third stage appropriates as its own share of the universal body only what it in the earthly realm has developed and accomplished. What a man has changed in this world by his77 life in it, that constitutes his further life in the universal existence.

This consists partly of definite accomplishments and deeds, partly of actions continuously recurring, just as the earthly body is made up of fixed parts and of parts which are movable and supported by the fixed ones.

All life circles of the higher spirits intersect each other, and you ask how it is possible that such numberless circles can intersect without disturbance, error, or confusion.

Ask rather first, how it is possible that innumerable undulations in the same pond, waves of sound in the same air, waves of light in the same ether, pulses of memory in the same mind intersect, that, finally, the countless life circles of man, bearing their78 great future, already in this life intersect without disturbance, error, or confusion. Rather a far higher plane of life and growth is achieved through these vibrations and memories reaching from this present life to the one beyond.

But what separates the circles of consciousness which cross each other?

Nothing separates them in any of those details in which they cross each other; they have all characteristics in common; only each stands in different relations from the other; that separates them in general and distinguishes them in their higher individuality. Ask again what distinguishes or separates circles which intersect; nothing separately; yet you easily observe an outward difference yourself in general; still more79 easily will centers which are themselves self-conscious also distinguish an inner difference.

Perhaps you have sometimes received from a distant place a letter written across both ways. How do you decipher both writings? Only by the coherence which each has in itself. In like manner is crossed the spiritual handwriting with which the page of the world is filled; and each is read by itself, as if it occupied the whole space, and the others, too, which overlie it. Not merely two, but innumerable letterings make a network of record on the earth; the letter, however, is but an inadequate symbol of the world.

Still, how can consciousness continue to preserve its unity in so large an extension80 of its ground, how withstand the law of the threshold of consciousness?5

5. This empirical law of the relation between body and soul consists in the fact that consciousness everywhere ceases, if the bodily activity upon which it depends sinks below a certain degree of strength, which is called the threshold. Now in proportion as it extends itself more widely, can it the more easily, on account of the accompanying weakness, fall below this level. As the total consciousness has its threshold, which makes the dividing line between sleeping and waking in the whole man, so, too, is it with the details of consciousness, whence it comes that during waking now this, now that idea presents itself or sinks out of sight, according as the particular activity upon which it depends rises above or sinks below the special threshold. (Compare Elem. der Psychophysik, Kap. X, XXXVIII, XXXIX, and XLII.)

Ask first, how it can preserve its unity in the smaller expanse of the body, of which the larger one is only the continuation. Is, then, your body, is your81 brain a point? or is there a central spot within as seat of the soul? No.6 As it is now the nature of the soul to maintain the limited composite of your body, so in the future will it be to unite the greater composite of the greater body. The divine spirit knits together, indeed, the whole fabric of the world; or would you seek even for God in one point? In that other world you will only acquire a larger part of His omnipresence.

6. Concerning this, compare Elemente der Psychophysik, Kap. XXXVII, and Atomenlehre, Kap. XXVI.

If you fear that the wave of your future life will not in its extension reach the threshold which here it surmounts, remember that it does not spread itself into an empty world, then, indeed,82 would it sink helplessly into an abyss, — but into a realm, which, as the eternal foundation of God, at the same time becomes the foundation of your life, for only in virtue of the divine life is the creature able to live at all.7

7. In order not to permit an apparent contradiction of the above mentioned speculation to the psychophysical doctrine of the combined threshold (upon which the most enlightening word is in Wundt’s philos. Stud., IV, s. 204 u. 211), note the following: If the psychophysical life wave (to continue the use of this concise expression) of man, made up of components of the most manifold sort, should spread out into a world which contained only different components, then, indeed, must it be assumed that it, in its extension, would fall below the combined threshold here under consideration. Since, however, the psychophysical undulatory sea of the universe, among its other components, comprehends also such as are like to those of the human life wave, and indeed of the most varying height or intensity, therefore such as already rise above or come near the level of the combined threshold and are only raised still higher by the similar ones which join them, so is the result of the above speculation placed on a somewhat more solid basis. (Note to the third edition.)